¿Quién tiene derechos históricos?

90% DE ISRAELÍES Y ÁRABES NO SON ORIUNDOS DE PALESTINA

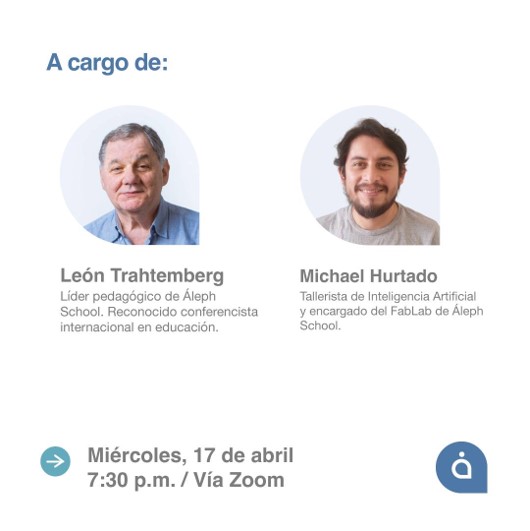

Por León Trahtemberg, 17/08/2014

90% de judíos y árabes cristianos y musulmanes que viven en lo que hoy se denomina Israel y Palestina no tienen ancestros que hayan vivido más de 5 generaciones en esa zona.

La Palestina del Imperio Turco Otomano (1299-1922) y del Mandato Británico (1922-1948 incluyendo a las actuales Israel+Autoridad Palestina+Jordania) era una zona desértica y/o pantanosa, con algunas comunidades judías y árabes viviendo dispersas por esa provincia del Imperio Otomano. Al lado de núcleos de judíos que habitaron continuamente la zona desde la época bíblica, hubo también núcleos de árabes cristianos (desde la era de Jesús) y árabes musulmanes (desde la era de Mahoma) que vivieron continuamente en la región denominada Palestina por los romanos. Pero la gran mayoría de los ocupantes de esas tierras desde fines del siglo XIX en adelante fueron emigrantes de diversas partes del mundo que llegaron allí como producto de guerras y persecuciones de gobiernos y poblaciones hostiles de los países de los que eran oriundos. En el caso judío, principalmente de Rusia desde 1880 a los que se sumaron europeos de diversos países a raíz del advenimiento del nazismo. Debían pagar impuestos especiales a los turcos para poder residir allí. En el caso de los musulmanes, eran migrantes de la guerra de Crimea (1853-6), la derrotada Bosnia y Herzegovina a mano del imperio cristiano Austrohúngaro (1878) y el desmembrado imperio otomano en la I Guerra Mundial (1914-1918). (También migraron a Anatolia, Armenia, Líbano y Siria). Para asentarse en Palestina recibieron incentivos del sultán turco otomano que incluían tierras gratuitas, 12 años de exoneración de impuestos y exención del servicio militar.

Con la ocupación franco inglesa de buena parte del derrotado Imperio Otomano reducido a la actual Turquía es que nacen casi todos los países que se conocen hoy en el Medio Oriente.

Inglaterra pactó en 1916 la sublevación de los distintos grupos árabes del Medio Oriente contra los turcos, a cambio de la promesa de una futura posesión e independencia de esos territorios, con lo que evitaron que India, Sudán, Egipto, Marruecos, Argelia y Túnez se alíen con los turcos. Además, secretamente Inglaterra se repartió con Francia sus áreas de influencia por el tratado de Sykes Picot dejando Líbano y el sur de Turquía (Siria) a cargo de Francia, manteniendo los británicos su influencia al sur del paralelo 29: casi toda Arabia, Kuwait, los emiratos del Golfo Pérsico y Yemen. Pero esas promesas solo serían viables con el apoyo del soberano hashemita Hussein de La Meca. Éste en 1915 encomendó a su hijo mayor Alí que comprometiera a las diversas tribus del emirato, envió a su hijo Faisal a Damasco para levantarse contra los sirios que combatían en las filas otomanas y encargó a su hijo Abdallah la coordinación con los británicos para formalizar el compromiso de que con el Imperio Otomano derrotado, sus posesiones pasarían a su control.

Con motivo de la derrota del Imperio Alemán y el Imperio Otomano en la 1era Guerra Mundial (1918) la Sociedad de Naciones otorgó a las potencias triunfadoras Inglaterra y Francia un Mandato sobre los territorios coloniales del Imperio alemán y las antiguas provincias del Imperio otomano para su administración y en algunos casos su eventual independencia (Artículo 22 del Tratado de Versalles de 1919).

Los mandatos fueron vistos como colonias de facto por estas potencias que dieron origen a Irak (entregado a Feisal, independizado de Gran Bretaña en 1932); Siria (independizado de Francia en 1946); Líbano (Independizada de Francia en 1943) y Palestina (dividida por Gran Bretaña en 1922 para excluir a Transjordania -entregada a Abdallah- que se independizó en 1946 con el nombre de Jordania). El resto de Palestina fue repartida en 1947 en dos, para crear un estado judío (1948) y un estado palestino (que no nació formalmente hasta 1988 por acuerdo de la ONU).

En la península Arábiga se constituyó en 1918 el reino de Yemen del Norte y en 1932 el reino unificado de Arabia Saudita. En cuanto a los países del golfo Pérsico y nor-África éstos se independizaron del mandato británico también en esas décadas: Omán (1940), Libia (1951, previa colonia de Italia hasta IIGM), Sudán (1956), Kuwait (1961), Bahréin (1971), Yemen del Sur (1967), Qatar (1971), Emiratos Árabes Unidos (1971). En esos casos la independencia de las monarquías o emiratos fue una concesión de los británicos a las familias dominantes de cada región con las cuales garantizaba una relación política y comercial privilegiada. En pocos casos la independencia fue producto de rebeliones anti coloniales: Túnez (1955 contra Francia), Argelia (1962 contra Francia) y Marruecos (1956 contra España y Francia)

COROLARIO:

Cuando se habla de derechos históricos de judíos o árabes palestinos a la tierra de la Palestina histórica hay que considerar que es un concepto sumamente difuso y que en todo caso la formalización del derecho internacional a su existencia independiente es tan contemporáneo como lo es la existencia de todos los países de nor-África y el Golfo Pérsico.

En el caso de Palestina la pregunta es ¿Dónde se coloca el punto de partida histórico para tal juicio? El más reciente es el mandato británico, que da derechos de residencia similares a ambos pueblos (Declaración Balfour de 1917). En el imperio turco otomano de los 700 años previos, hubo presencia de ambos pueblos. Podemos remontarnos a las cruzadas, o previamente al surgimiento del Islam, o antes aún a la época de Jesús y podemos llegar inclusive hasta la Biblia y seguirá la discusión sobre la decisión del Patriarca Abraham de dar continuidad al pueblo hebreo en Canaán a través de Itzjack hijo de su esposa Sarah y expulsar de esas tierras a su otro hijo Ismael, hijo de la esclava Agar (a quien los árabes consideran su primer antecesor).

Al final de cuentas, los derechos históricos podrán ser debatidos por los académicos hasta el final de los tiempos. El hecho real es que en la zona que alguna vez se denominó Palestina vivían y viven judíos y árabes cristianos y musulmanes que tienen que aceptarse como pueblos (y estados) vecinos, y aprender a convivir en paz.

The Invention of Middle East Nation-States

August 26, 2014 By George Friedman STRATFOR

Lebanon was created out of the Sykes-Picot Agreement. This agreement between Britain and France reshaped the collapsed Ottoman Empire south of Turkey into the states we know today — Lebanon, Syria and Iraq, and to some extent the Arabian Peninsula as well. For nearly 100 years, Sykes-Picot defined the region. A strong case can be made that the nation-states Sykes-Picot created are now defunct, and that what is occurring in Syria and Iraq represents the emergence of those post-British/French maps that the United States has been trying to maintain since the collapse of Franco-British power.

Sykes-Picot, named for French diplomat Francois Georges-Picot and his British counterpart, Sir Mark Sykes, did two things. First, it created a British-dominated Iraq. Second, it divided the Ottoman province of Syria on a line from the Mediterranean Sea east through Mount Hermon. Everything north of this line was French. Everything south of this line was British. The French, who had been involved in the Levant since the 19th century, had allies among the region’s Christians. They carved out part of Syria and created a country for them. Lacking a better name, they called it Lebanon, after the nearby mountain of the same name.

The British named the area to the west of the Jordan River after the Ottoman administrative district of Filistina, which turned into Palestine on the English tongue. However, the British had a problem. During World War I, while the British were fighting the Ottoman Turks, they had allied with a number of Arabian tribes seeking to expel the Turks. Two major tribes, hostile to each other, were the major British allies. The British had promised postwar power to both. It gave the victorious Sauds the right to rule Arabia — hence Saudi Arabia. The other tribe, the Hashemites, had already been given the newly invented Iraqi monarchy and, outside of Arabia, a narrow strip of arable ground to the east of the Jordan River. For lack of a better name, it was called Trans-Jordan, or the other side of the Jordan. In due course the «trans» was dropped and it became Jordan.

And thus, along with Syria, five entities were created between the Mediterranean and Tigris, and between Turkey and the new nation of Saudi Arabia. This five became six after the United Nations voted to create Israel in 1947. The Sykes-Picot agreement suited European models and gave the Europeans a framework for managing the region that conformed to European administrative principles. The most important interest, the oil in Iraq and the Arabian Peninsula, was protected from the upheaval in their periphery as Turkey and Persia were undergoing upheaval. This gave the Europeans what they wanted.

What it did not do was create a framework that made a great deal of sense of the Arabs living in this region. The European model of individual rights expressed to the nation-states did not fit their cultural model. For the Arabs, the family — not the individual — was the fundamental unit of society. Families belonged to clans and clans to tribes, not nations. The Europeans used the concept of the nation-state to express divisions between «us» and «them.» To the Arabs, this was an alien framework, which to this day still competes with religious and tribal identities.

The states the Europeans created were arbitrary, the inhabitants did not give their primary loyalty to them, and the tensions within states always went over the border to neighboring states. The British and French imposed ruling structures before the war, and then a wave of coups overthrew them after World War II. Syria and Iraq became pro-Soviet states while Israel, Jordan and the Arabians became pro-American, and monarchies and dictatorships ruled over most of the Arab countries. These authoritarian regimes held the countries together.

Reality Overcomes Cartography

It was Lebanon that came apart first. Lebanon was a pure invention carved out of Syria. As long as the Christians for whom Paris created Lebanon remained the dominant group, it worked, although the Christians themselves were divided into warring clans. But after World War II, the demographics changed, and the Shiite population increased. Compounding this was the movement of Palestinians into Lebanon in 1948. Lebanon thus became a container for competing clans. Although the clans were of different religions, this did not define the situation. Multiple clans in many of these religious groupings fought each other and allied with other religions.

Moreover, Lebanon’s issues were not confined to Lebanon. The line dividing Lebanon from Syria was an arbitrary boundary drawn by the French. Syria and Lebanon were not one country, but the newly created Lebanon was not one country, either. In 1976 Syria — or more precisely, the Alawite dictatorship in Damascus — invaded Lebanon. Its intent was to destroy the Palestinians, and their main ally was a Christian clan. The Syrian invasion set off a civil war that was already flaring up and that lasted until 1990.

Lebanon was divided into various areas controlled by various clans. The clans evolved. The dominant Shiite clan was built around Nabi Berri. Later, Iran sponsored another faction, Hezbollah. Each religious faction had multiple clans, and within the clans there were multiple competitors for power. From the outside it appeared to be strictly a religious war, but that was an incomplete view. It was a competition among clans for money, security, revenge and power. And religion played a role, but alliances crossed religious lines frequently.

The state became far less powerful than the clans. Beirut, the capital, became a battleground for the clans. The Israelis invaded in order to crush the Palestinian Liberation Organization, with Syria’s blessing, and at one point the United States intervened, partly to block the Israelis. When Hezbollah blew up the Marine barracks in Beirut in 1983, killing hundreds of Marines, U.S. President Ronald Reagan, realizing the amount of power it would take to even try to stabilize Lebanon, withdrew all troops. He determined that the fate of Lebanon was not a fundamental U.S. interest, even if there was a Cold War underway.

The complexity of Lebanon goes far beyond this description, and the external meddling from Israel, Syria, Iran and the United States is even more complicated. The point is that the clans became the reality of Lebanon, and the Lebanese government became irrelevant. An agreement was reached between the factions and their patrons in 1989 that ended the internal fighting — for the most part — and strengthened the state. But in the end, the state existed at the forbearance of the clans. The map may show a nation, but it is really a country of microscopic clans engaged in a microscopic geopolitical struggle for security and power. Lebanon remains a country in which the warlords have become national politicians, but there is little doubt that their power comes from being warlords and that, under pressure, the clans will reassert themselves.

Syria’s Geographic Challenge

Repeats in Syria and Iraq

A similar process has taken place in Syria. The arbitrary nation-state has become a region of competing clans. The Alawite clan, led by Bashar al Assad (who has played the roles of warlord and president), had ruled the country. An uprising supported by various countries threw the Alawites into retreat. The insurgents were also divided along multiple lines. Now, Syria resembles Lebanon. There is one large clan, but it cannot destroy the smaller ones, and the smaller ones cannot destroy the large clan. There is a permanent stalemate, and even if the Alawites are destroyed, their enemies are so divided that it is difficult to see how Syria can go back to being a country, except as a historical curiosity. Countries like Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Israel and the United States might support various clans, but in the end, the clans survive.

Something very similar happened in Iraq. As the Americans departed, the government that was created was dominated by Shia, who were fragmented. To a great degree, the government excluded the Sunnis, who saw themselves in danger of marginalization. The Sunnis consisted of various tribes and clans (some containing Shiites) and politico-religious movements like the Islamic State. They rose up in alliance and have now left Baghdad floundering, the Iraqi army seeking balance and the Kurds scrambling to secure their territory.

It is a three-way war, but in some ways it is a three-way war with more than 20 clans involved in temporary alliances. No one group is strong enough to destroy the others on the broader level. Sunni, Shiite and Kurd have their own territories. On the level of the tribes and clans, some could be destroyed, but the most likely outcome is what happened in Lebanon: the permanent power of the sub-national groups, with perhaps some agreement later on that creates a state in which power stays with the smaller groups, because that is where loyalty lies.

The boundary between Lebanon and Syria was always uncertain. The border between Syria and Iraq is now equally uncertain. But then these borders were never native to the region. The Europeans imposed them for European reasons. Therefore, the idea of maintaining a united Iraq misses the point. There was never a united Iraq — only the illusion of one created by invented kings and self-appointed dictators. The war does not have to continue, but as in Lebanon, it will take the exhaustion of the clans and factions to negotiate an end.

The idea that Shia, Sunnis and Kurds can live together is not a fantasy. The fantasy is that the United States has the power or interest to re-create a Franco-British invention crafted out of the debris of the Ottoman Empire. Moreover, even if it had an interest, it is doubtful that the United States has the power to pacify Iraq and Syria. It could not impose calm in Lebanon. The triumph of the Islamic State would represent a serious problem for the United States, but no more than it would for the Shia, Kurds and other Sunnis. As in Lebanon, the multiplicity of factions creates a countervailing force that cripples those who reach too far.

There are two issues here. The first is how far the disintegration of nation-states will go in the Arab world. It seems to be underway in Libya, but it has not yet taken root elsewhere. It may be a political formation in the Sykes-Picot areas. Watching the Saudi peninsula will be most interesting. But the second issue is what regional powers will do about this process. Turkey, Iran, Israel and the Saudis cannot be comfortable with either this degree of fragmentation or the spread of more exotic groups. The rise of a Kurdish clan in Iraq would send tremors to the Turks and Iranians.

The historical precedent, of course, would be the rise of a new Ottoman attitude in Turkey that would inspire the Turks to move south and impose an acceptable order on the region. It is hard to see how Turkey would have the power to do this, plus if it created unity among the Arabs it would likely be because the memories of Turkish occupation still sting the Arab mind.

All of this aside, the point is that it is time to stop thinking about stabilizing Syria and Iraq and start thinking of a new dynamic outside of the artificial states that no longer function. To do this, we need to go back to Lebanon, the first state that disintegrated and the first place where clans took control of their own destiny because they had to. We are seeing the Lebanese model spread eastward. It will be interesting to see where else its spreads.